The Written Words of a Ledger Account are Transformed into a New ‘Masterpiece’ for Ruinart

Ruinart, the world's oldest champagne house, has a very special relationship with the world of contemporary art: asides from its role as an official partner of some of the most prestigious art fairs worldwide, the Maison also collaborates with international artists in the creation of new works. An example of one of its collaborations includes its ‘Masterpieces’ series, whereby the champagne house invites artists to create works of art inspired by its history, legacy and exquisite vintages. In fact, this long tradition of artistic collaborations dates as far back as 1895 (other contemporary artists who have participated in the Maison’s ‘Masterpieces’ initiative include Gideon Rubin, Rubén Fuentes and Piet Hein Eek).

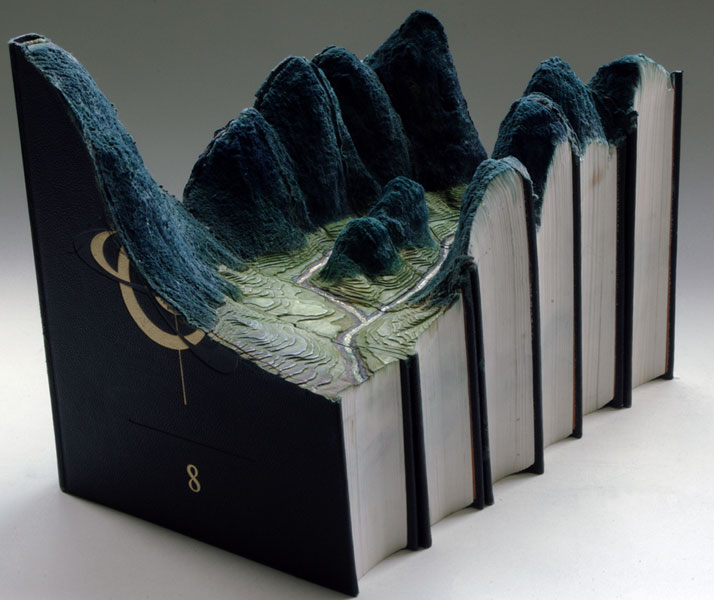

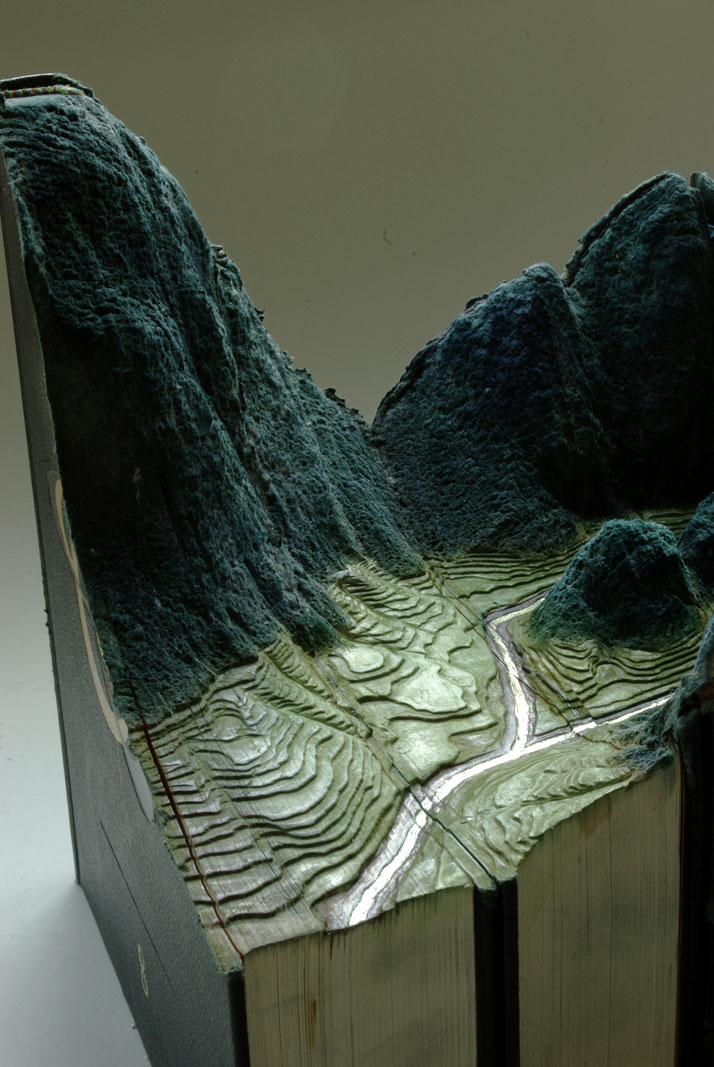

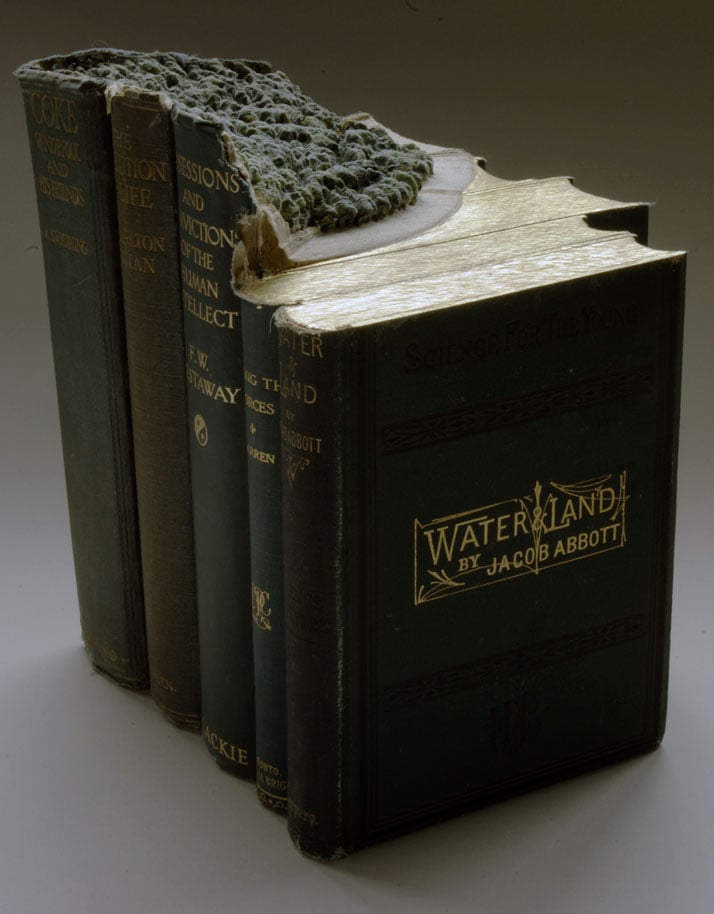

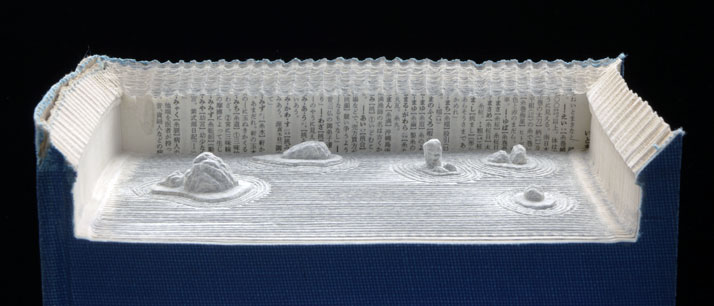

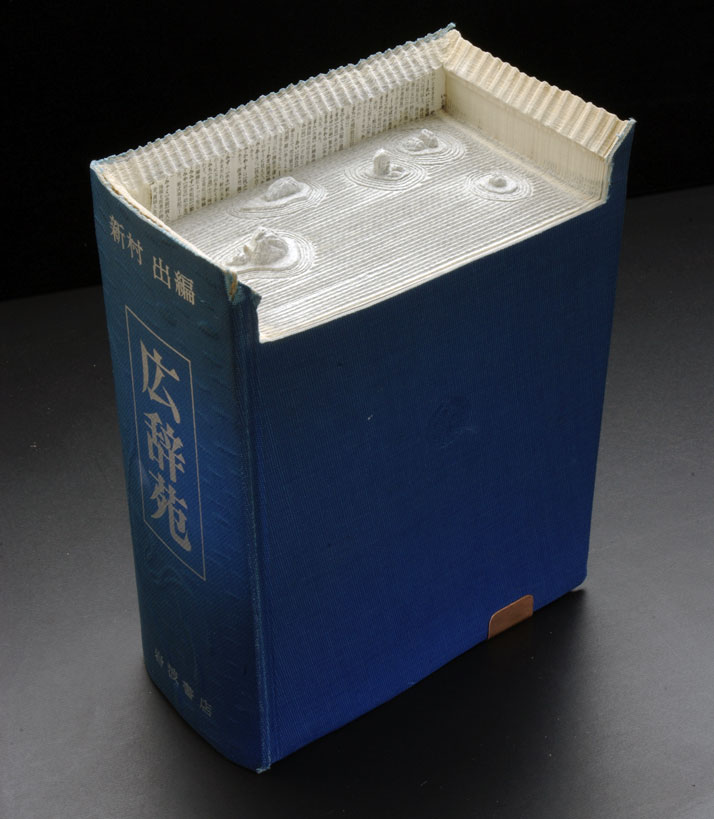

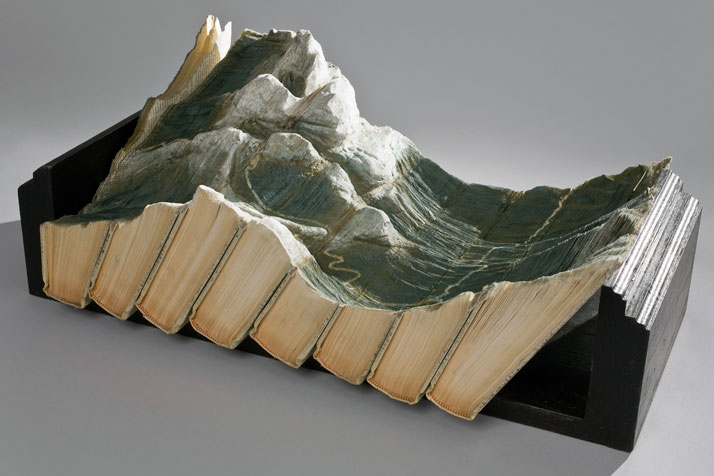

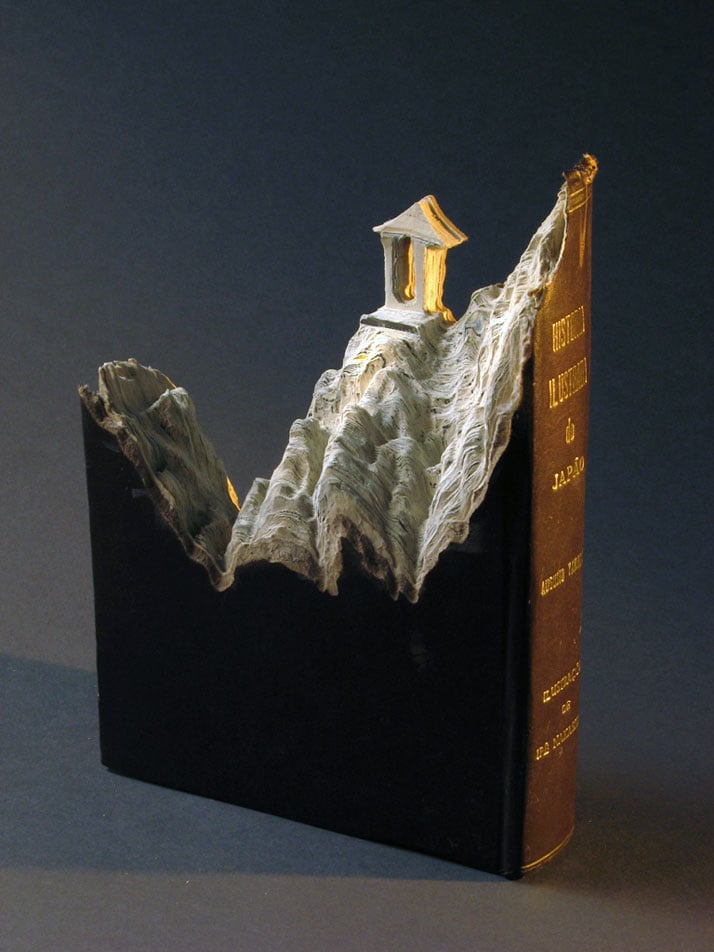

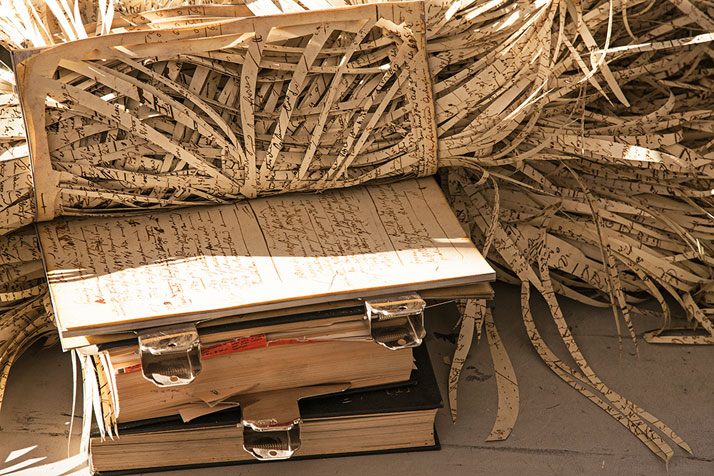

For its latest ‘Masterpiece’, Ruinart invited Scottish visual artist Georgia Russell to bring her unique technique and artistic vocabulary and add it to the Maison’s heritage. Russell, who now lives and works in France, has come to be known for her technique of cutting and shaping printed paper, especially books and sourced photographs, by use of a sharp scalpel, in order to create intricate flowing patterns that (at least in the case of the books) appear to flow out of their covers creating rich textures and surreal shapes that spark our imagination.

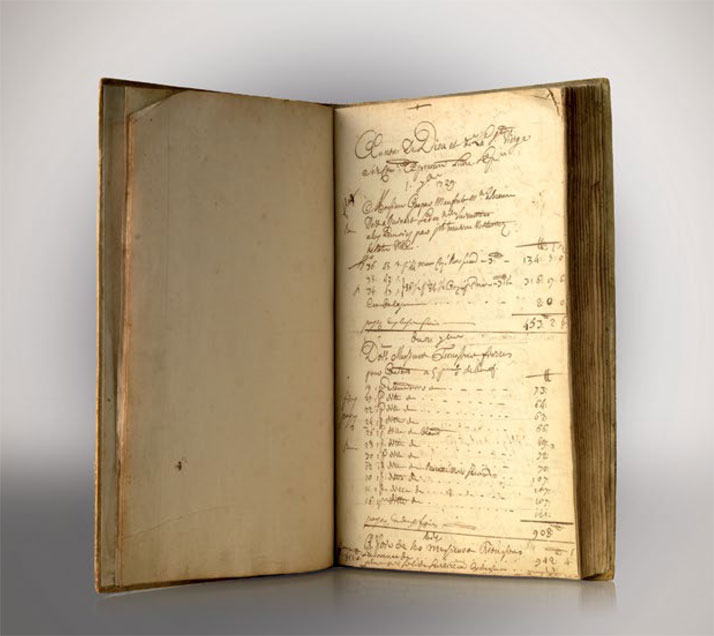

Russell chose to work on one of Ruinart’s most precious relics, the Grand Livre: the 1729 book containing the Maison’s founding act and early achievements, written by no other than Nicolas Ruinart the founder of the venerable House. Based on a facsimile of the book that was given to Russell, she then went on to painstakingly carve each and every page to create an intricate foliage that gracefully pours out of the book, merging the elegant handwriting with the light. The work also pays tribute to Ruinart’s ancient wine cellars which are comprised of a vast network of tunnels and cathedrals of chalk, all carved patiently and laboriously by hand over many centuries. Patterns on the walls of Ruinart’s cellars provided the inspiration for a delicate ornament for the Maison’s flagship Blanc de Blancs wine, (also designed by Russell which we presented on Yatzer back in April).

As the Official Champagne Partner for Art Basel 2014, Ruinart presented Georgia Russell’s ‘Masterpiece’ together with her ornament for the Maison’s Blanc de Blancs bottle at the Ruinart VIP Lounge.

source : https://www.yatzer.com/written-words-ledger-account-are-transformed-new-‘masterpiece’-ruinart